Abdulhamit Bilici: How Turkey Lost its Largest Newspaper

Abdulhamit Bilici was the editor-in-chief of Zaman, the largest newspaper in Turkey, before it was taken over by the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Fired and receiving threats of imprisonment, he fled to Northern Virginia.

“I was supposed to report about his campaign when he was running for office as mayor of

Istanbul,” Bilici said. “These were the early days of my career in journalism.”

Zaman was created in 1986, before Erdogan was a high-profile politician.

“Our idea was to be open to the world and to make Turkey a part of EU, to be a real democracy,” Bilici said. “…to make a kind of marriage between secular approach and the religious approach.”

In the early days of his career, Erdogan ran on a platform of political Islamism, which ties politics to religion.

“It stands for grabbing political power and imposing that understanding of religion–Islam in that case–on society, and it didn’t have a sincere approach to democracy,” Bilici said. “It was seeing democracy as, you use it until you reach your destination, and then you leave it–a very opportunistic approach to democracy.”

However, before Erdogan founded his political party, the Justice and Development Party, in 2001, he changed his ideology, and left political Islamism behind.

“As a journalist, I was supportive of him, and my newspaper was very much supporting that approach which was very much identical to our editorial understanding,” Bilici said. “We believed that he really transformed and he was sincere and he got rid of his old legacy.”

Erdogan took a secular approach to politics for ten years after he announced his ideological shift.

“Turkey became a shining star in the world,” Bilici said. “Turkey was seen as a good example for the whole muslim world, and there aren’t many examples to show that you could be Muslim and democratic at the same time.”

Bilici stressed the idea of Turkey being able to unite different parts of the world.

“Turkey is a bridge between Asia and Europe, it is a bridge between the Christian world and the Muslim world, and it is a bridge modern values and traditional values,” Bilici said. “With that function, these politics were just overlapping and making very big strides for the country.”

Bilici called these years the Golden Age of Turkey.

“Turkey’s economy was booming, Turkey’s popularity was booming, both in the west and in the Muslim world at the same time.”

This “Golden Age” came to an end when Erdogan changed his ways.

“There were lots of different opinions, and they were coming together around the table, and making very humble and very rational decisions,” Bilici said. “But when he alienated others from his circle within party, he became one man in the party and started to target, to aim, to be one man in the country because he was too powerful.”

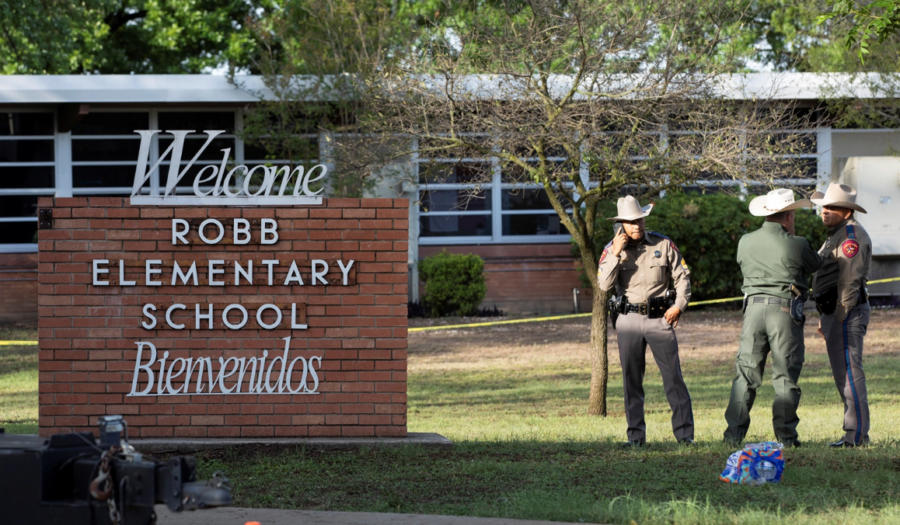

The Turkish public were used to the country being run as a democracy, so when the government made plans to build a shopping mall on Gezi Park, one of the only green areas of Istanbul, the public organized protests.

“To their surprise, Erdogan, instead of listening to their concerns, crushed the protests by brutal police force,” Bilici said.

CNN International, BBC News, and other media sites broadcasted this event, but the Turkish channels did not.

“The Turkish TV channel, which is affiliated with CNN in Turkey, and CNN Turk were not able to broadcast these protests, but they were broadcasting instead, a documentary about penguins,” Bilici said.

This was the beginning of the media take-over by the government under Erdogan.

“Since then, Erdogan started to be very harsh against anyone who dares to be critical of his totalitarianism, newly emerging totalitarian and autocratic approaches,” Bilici said. “He was making phone calls to the owners of the newspapers and television channels, to fire the critical columnists and reporters; lots of my friends were fired from different media outlets just because of their critical approach.”

Bilici was amazed at how Erdogan turned on the media, especially Zaman, with which he did exclusive interivews.

“I was making interviews with him, I was flying on his plane, I was very close to him in those good golden times,” Bilici said. “But then… we were targeted by his wrath. He started to quarrel and he tried to belittle and intimidate our reporters in front of cameras, our own journalists that are working with me for my newspaper.”

The media did not stop asking questions about his corruption allegations, despite the initial threats, which led Erdogan to take drastic measures.

“When he was not able to stop those questions, and change our … editorial line, so he cancelled our reporter’s right to cover press conferences and cancelled the press cards of our reporters, and then made public calls to boycott our newspaper, not to buy the newspaper, and then he sent frequently tax inspectors to pressure our financial system and then made phone calls to business companies not to purchase advertisement from us” Bilici said.

Zaman continued to be critical of Erdogan despite his efforts to silence the newspaper, so he used what Bilici dubbed “the nuclear approach.” He used courts he controlled to seize control of the media corporation Zaman was a part of.

“The building was surrounded by our readers who came to support us and our staff,” Bilici recalls. “Their relatives came to support them, some of the children and wives and mothers–my dad even came.”

The police attempted to take over the building.

“There was brutal crash against those civilian protests by tear gas and water cannons,” Bilici said. “They cut the iron gate of the building and they started to come, step by step, into the building and started to kick out the news reporters, the families, the staff, and everyone.”

Bilici was on the 4th floor with his fellow columnists and trying to figure out what to do when the police came. Bilici remembers that they were “in solidarity.”

“The resistance continued until 1:30 am,” Bilici said. “They pushed me out, together with my deputies, my friends, reporters and colleagues, so we went with empty hands, with trauma and shock.”

Bilici had been working at Zaman since 1993.

“For me, it was more than my home, and for lots of my friends and colleagues.”

Bilici woke up the next morning and headed to work as he would any other day.

“I came and I was stopped in front of the newspaper by the police because the building was surrounded by police officers, a huge number of police officers, and they said ‘You are not allowed.’”

Bilici was fired on the spot, but was allowed in the building briefly.

“Some of the staff were there–they came also with difficult conditions,” Bilici said. “They showed their huge support to me–they were chanting, ‘Bilici in! Trustees out!’… but I was fired and there was nothing to do, so I left.”

The new editor, hired from a “xenophobic radical newspaper,” fired anyone who didn’t comply with his instructions.

“They changed the editorial policy in 24 hours; we were a critical newspaper and it became a mouthpiece of Erdogan,” Bilici said. “In protest, our readers stopped buying the newspaper, so the circulation was 600,000 and in one week it was down to 5,000.”

Bilici’s termination didn’t end his conflict with the government.

“I was getting lots of threats that I’ll end up in jail,” Bilici said. “I was always [receiving] the message ‘prepare your bag for prison.’”

Bilici had to leave the country, which was difficult because he didn’t know if he had a valid passport.

“I was not able to ask anyone because the government was seeing me as an enemy,” Bilici said. “I could only try by going to the airport.”

Bilici was able to leave, first to Europe and then to Washington, D.C. He couldn’t bring his family along until seven months later.

“This is the fortunate part, that I’m safe at least, and I’m together with the members of my family (my son, my daughter, and my wife),” Bilici said. “But the unfortunate side is that 50 of my friends are in jail now, or are trapped.”

After the coup that occurred in July of 2016, the government destroyed Zaman, as well as shut down 200 other media outlets: TV channels, radio, websites, etc. With 200 journalists imprisoned, Turkey is now the leading country in terms of jailing journalists.

“This is a country which is a member of NATO, which is an ally of United States for more than 60 years, which tries to be part of the European Union, which is a founding member of European Counsel, all of which require Turkey to be a democracy, to respect freedom of expression and freedom of media,” Bilici said. “But Turkey is drifting away, and now it’s very difficult to call it a democracy.”

Bilici feels that, in addition to hurting Turkey, the shifts towards authoritarianism is a loss for the world.

“This is… a very sad story of how a country that could play a role of moderate Muslim democracy as a model for the Muslim world and a country that could play a role as a bridge between different worlds (Christians and Muslims, the West and the East, Asia and Europe) turned into a country that is now itself a problem,” Bilici said. “And it happened in maybe four or five years.”

The speed of this transition astounded Bilici, and makes the future hard to predict.

“You know, if I went back four years or five years ago when I was very close to Erdogan and supporting him, it’s impossible to imagine that it could come to this point,” Bilici said. “so I don’t know what shape Turkey will be in in five years.”

Bilici considers there to be two options for the future.

“This authoritarianism could be established as a state model… and Turkey could turn into Iran or Syria or other authoritarian countries,” Bilici said. “Or there could be an economic crash, and because of that, people could get away from supporting Erdogan, and then we could gradually return to normal.”

If the Turkey does establish itself as an authoritarian state, what would come of its alliances?

It would be the only country within NATO that is an autocracy–in NATO, there are not such countries,” Bilici said. “So, can Turkey continue to be part of the West and be an autocracy at the same time? This is open for debate.”

Bilici is hoping for the second option, in which Turkey could return to normal, because his “utopia” is to have Turkey be a model, as he’s stated before.

“My desire is for Turkey to have the potential to be both popular in the West and in the Muslim world at the same time. There are not many countries like that… The world needs such an example.”

When asked to compare Turkey’s situation to that of the United States, Bilici showed faith in the founding principles of America’s ability to keep the United States from following Turkey’s path.

“The first day they founded the [United States,] they saw that you can’t trust human nature, so you should create a system of checks and balances, and you should not give the authority and power to just one person.”

Bilici does, however, recognize some similarities in the two countries’ situations.

“There has been a quarrel between a CNN reporter and Trump that is similar to the early stages we witnessed in our own case. The reporter was belittled by Trump during a press conference.”

The difference was that another media source stood up for the reporter: a FOX anchorman stated that while they disagreed in politics, the CNN reporter’s press freedom should be protected.

“Some of our friends were persecuted when we were in good terms with Erdogan, and we made the mistake of not showing our solidarity with them; now, I am very sorry for that,” Bilici said. “I could have been more… democratic and said ‘Yes, I like Erdogan, but you cannot do this, this is not allowed, you cannot imprison journalists and stop them from covering press conferences.’”

Bilici sees some interactions between U.S. government and the media as similar to those in Turkey, but places faith in the system created by the founding fathers.

“If the system created by the founding fathers continues to function, and if the American society is aware to protect it, you will not have that problem.”

Bilici pinpointed two areas that are essential to preserving any democracy: the freedom of the press and the independence of the judiciary.

“If you want to protect democracy, you should be aware to protect press freedom,” Bilici said. “If judges are politicized, if the courts can make decisions in line with political views, that will make it very difficult for anyone to protect their rights.”

The U.S. Constitution protects freedom of press in the first amendment, but that doesn’t necessarily ensure its presence; it didn’t for Turkey.

“The courts should act in line with that Constitution, but they do not do that anymore, they act in line with Erdogan,” said Erdogan. “A good Constitution is not a guarantee; the important thing is whether it is observed or not.”

Protecting democracy is not solely the responsibility of the government. The public can contribute to its preservation by staying informed so that they won’t be fooled by propaganda, as some were in Turkey.

“Because there is a bombardment of information, the public should be knowledgeable about differentiating correct information from the fake,” Bilici said. “That is an important mission that should be accomplished by our education system. We should be careful readers.”

According to Bilici, the increase in technology and the simplicity of communication calls for greater measures taken to ensure an informed and sensible public.

“[Separating real news from fake news] requires a kind of intelligence and experience that, in my view, should be part of the curriculum in secondary school,” Bilici said. “All of us are now journalists. I can now message something, and it becomes news. In the past, it was just CNN, New York Times, etc. that were news sources; now every facebook user is media.”

His experiences have only strengthened his views on the free press and the merit of journalism.

“It is a stressful job, to be a journalist, because you decide to be a fighter for some good causes,” Bilici said. “It is not a job that you do 5 days a week from 9 to 5; it is a decision of life.”

I joined journalism my junior year because I loved writing and wanted to learn its other forms. This year, I'm the co-Editor-in-Chief, and I'm excited...

Amanda Ghiloni is a senior at West Potomac. It's her fourth year on The Wire. She enjoys doing graphic design for the print issues and helping teach the...

Cami joined journalism in her junior year because she loves writing. She has been a tutor in the West Potomac Writing Center since Sophomore year. This...

Nina Raneses • Oct 5, 2017 at 5:33 AM

This is such a good read on such an important topic!! Congrats on getting republished on that press freedom website. You deserve all that and more. Miss you all 🙂