#itooamwestpotomac: The Microaggression Theory

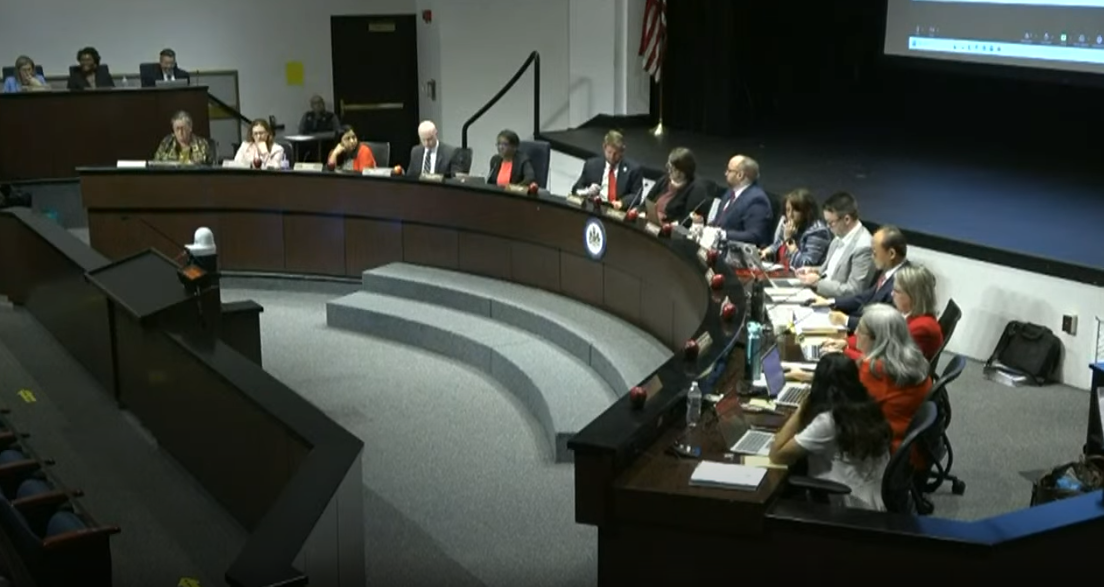

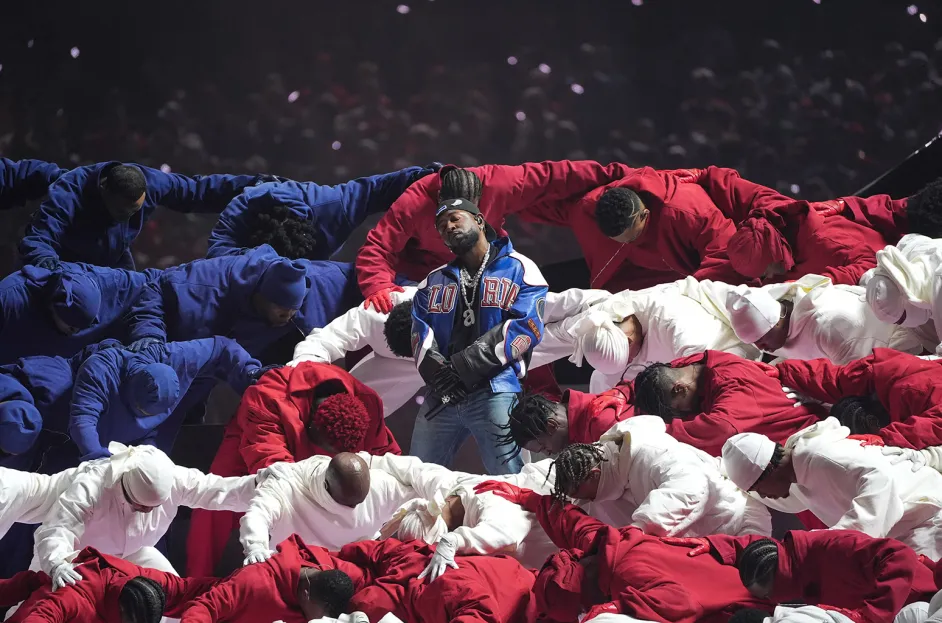

“Microaggressions” have become a catalyst for social rights activists’ projects across the world, spreading in the form of blogs, photo projects, and other social media

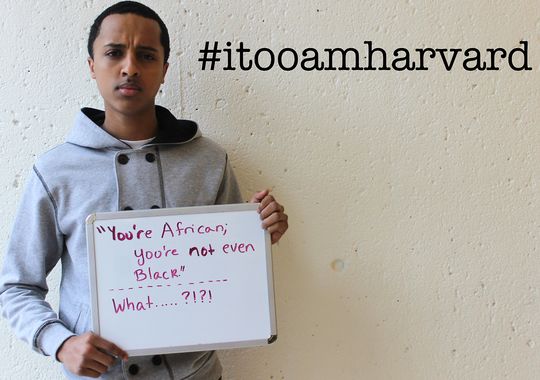

Courtesy of itooamharvard.tumblr.com

In a world regularly called “post-racial” and “progressive,” inequality and stereotyping is embedded in comments in nearly every conversation. These comments are both intentional and unintentional, and we often find ourselves either in the middle of giving one or receiving one.

This kind of behavior is known as “microaggression,” a term coined by Harvard psychiatrist Chester Middlebrook Pierce in the ‘70s. The original use of the word focused on racial microaggression, but today it describes unintended discrimination toward any marginalized group of people by race, gender, socioeconomic status, sexuality, or religion.

“Microaggressions” have become a catalyst for social rights activists’ projects across the world, spreading in the form of blogs, photo projects, and other social media. College campuses in particular have become a hotbed for all things microaggression, as students try to emphasize the negative impact unintended discrimination can have on a person’s overall personality and everyday life.

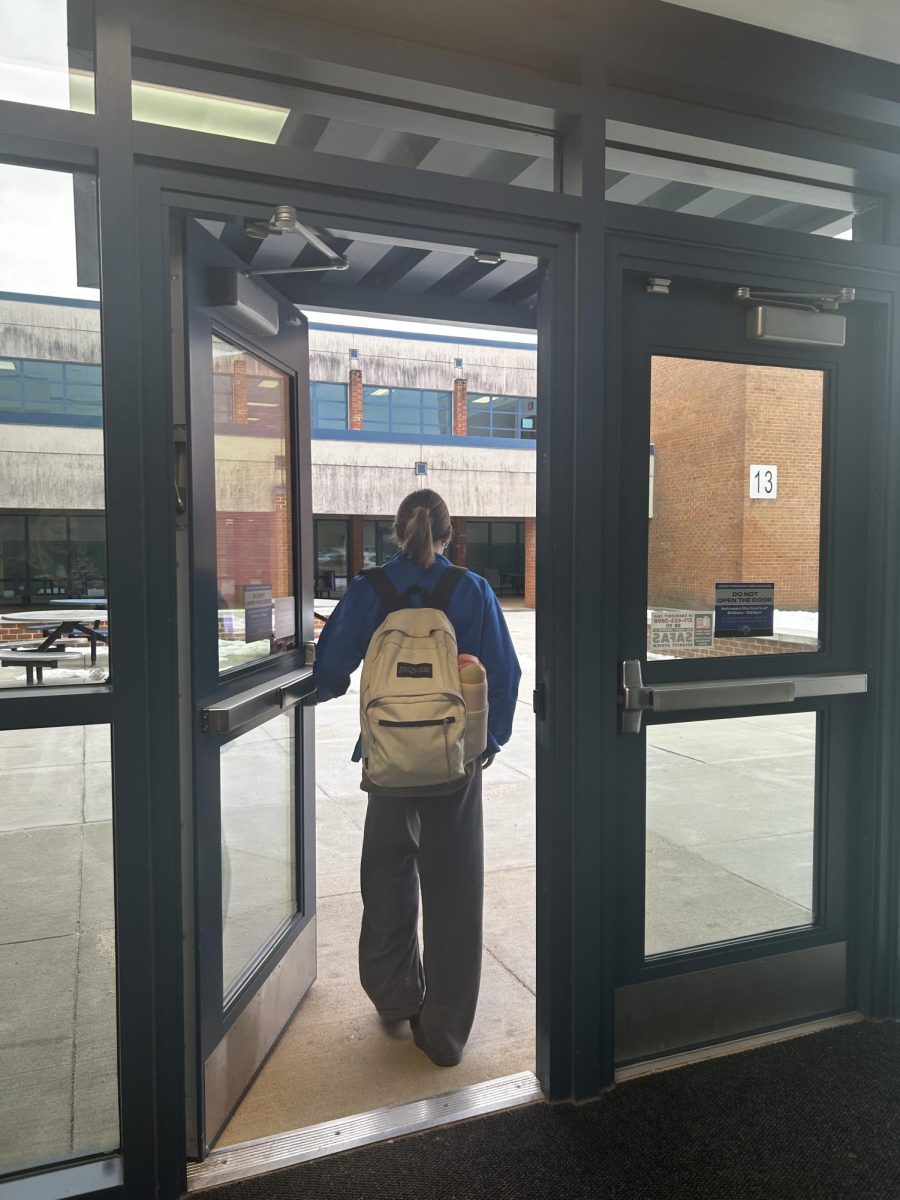

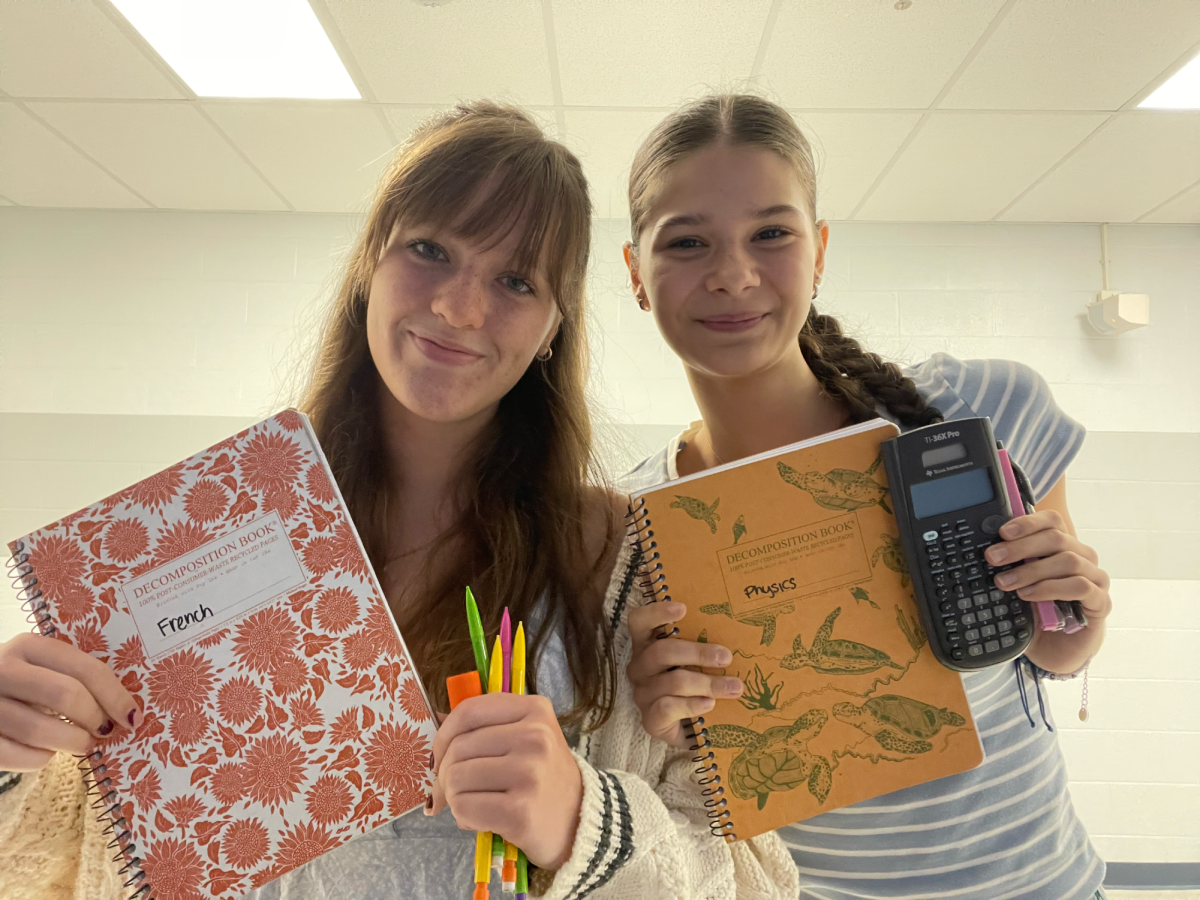

Like many of these college campuses, West Potomac has a diverse student population, one that reflects the demographic of the DC metro area. In a school of over 2,500, the student body is an incredible mix of many different ethnicities, cultures, and religions, made even more complex by the gaps in the socioeconomic status of various segments of the population. The numbers lead to one question: does diversity at West Potomac promote or discourage the microaggression problem?

Diversity can lead to either acceptance or prejudice. Microaggressions, however, are a form of prejudice disguised as what we believe is acceptance, even tolerance. Ultimately, it depends on what experiences a student has gone through that influences their answer. However, there is no doubt that instances of microaggressions are prevalent in our society, and they have even made their way into our school systems and the learning environment.

“Appalling and disgusting,” is how senior Rosie Afinyie, president of the Black Student Union, described how microaggressions have affected her. Originally from Ghana, she recounted her experience in American elementary school where her peers devalued her ethnicity after she told them she was African. “Africans,” they told her, were “not equivalent to black people,” and that “they’re different.” Afinyie says that those experiences growing up have made her the “blunt and straightforward” person she is today.

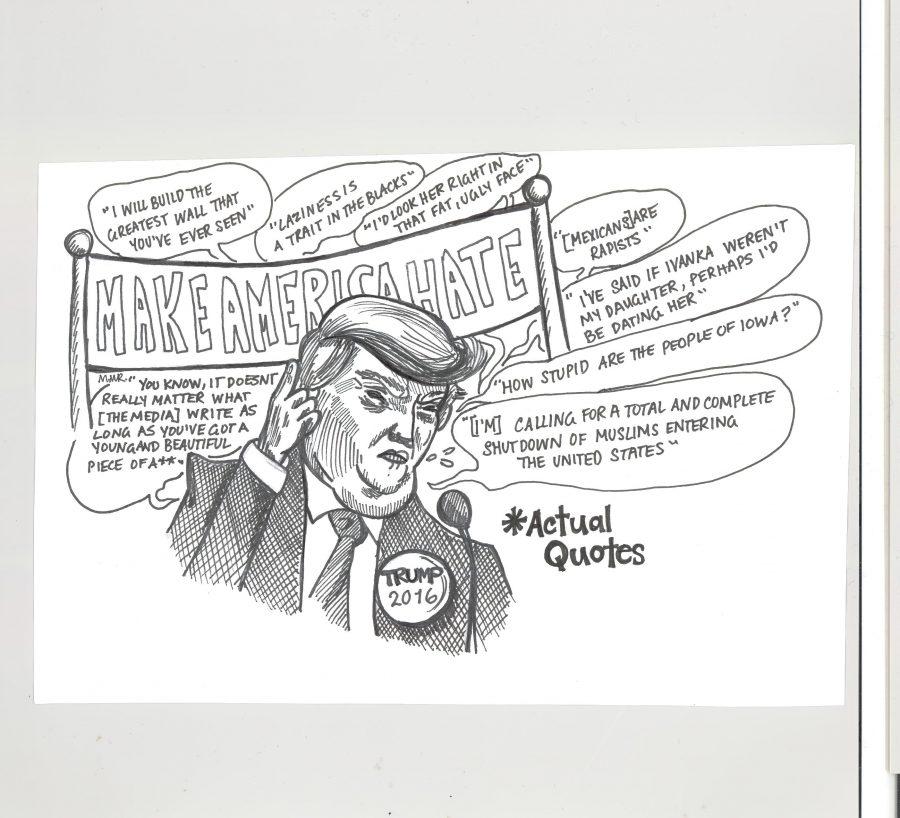

Various critics argue that microaggression theory is built around self-victimization and paranoia. This criticism ignores the fact that years and years of microaggression have negatively impacted so many in the marginalized groups that it is difficult to argue that they are championing their own victimization, or simply paranoid.

In both middle and high school, sophomore Shahtaj Ali has experienced countless microaggressions. As a Muslim, she says she’s felt like she’s had to explain the entire history of her religion for someone who is simply too lazy to pick up a book or do some research. Rather than simply dismissing these experiences as “ignorance is bliss,” Ali explains that she takes them very seriously. “Just because you think something is ‘ignorance is bliss’ doesn’t mean it’s easy living for someone else. Just because someone else is okay with having these things being said about them, doesn’t mean I will.”

However, she isn’t the only Muslim student to stand up for what she believes in. Senior Sebrine Abdulkadir, vice president of the Black Student Union, says she’s had people mistake her religion for her ethnicity. In middle school and early years of high school, she’s said she’s heard comments along the lines of “You’re Ethiopian? I thought you were Muslim,” and Islamophobic ones such as “Did you make a bomb last night?”

Most of those who experience microaggressions agree the best way to react to situations such as these is calmly and matter-of-factly. “As long as the way you approach the situation maturely and you’re not being rude about it,” says Abdulkadir, “it really depends on how you say things.”

Perspective and perception play the most crucial roles in microaggressive behavior. There are many underlying causes to how and why things are said, as Neftali Ruelas, club sponsor of Men With a Vision and a Purpose, will attest to.

His club puts young men in a leadership positions where they learn by serving the community, most recently at Belle View with at-risk students. Club members are trying to change how the Hispanic male is perceived in the local community.

“It’s not just the Hispanic culture, it’s not just socioeconomics, there’s just a lot more involved,” Ruelas explained. “A lot of these kids are living with grandma, and their parents are still living in El Salvador. There’s really a lot of underlying problems like immigration issues and things a lot of people don’t normally think about.”.

As Asian American Society, Black Student Union, and Men With a Vision and a Purpose provide support ethnicities and cultures, Gay Straight Alliance does the same with the full spectrum of sexuality and gender that is present at WestPo.

The vice president of GSA, who wishes to remain anonymous, says that he is constantly surrounded by a homophobic atmosphere on his sports team, and it makes it incredibly difficult to be himself around his teammates. Homophobic slurs and other offensive language is a common occurrence at practice, although they may not always realize it.

He adds that the majority of its members are in similar situations, and GSA’s “SafeSpace” conversations allow them to be themselves in a safe, judge-free and anonymous environment; their conversations never leave the room, but inside the walls, members openly discuss current events along with personal issues, one member even referring to club members as his family.

“There are a lot of people who can’t express themselves during the day,” he explains. “They have to be quiet for one reason or another. They can come in here and be themselves, talk, vent, and be who they are.”

The most important thing is that it’s up to every one of us to watch what we say to one another, intended or unintended. And if anything, it’s important to have people to talk to in order to stay level-headed.

While it’s important to note the progressiveness of diversity and equality in the media and in society, we still have a long way to go before prejudice is a thing of the past. The ‘micro’ in microaggression implies that these comments have small impact, but bigger issues such as race tensions, Islamophobia, and homophobia can stem from them. Underlying causes are important as well, and while it’s easy to denounce microaggression awareness as whining or paranoia–we need to think about the lives we’re ultimately impacting: our family, friends, and peers.