30 Years of History: The Creation of West Potomac High School

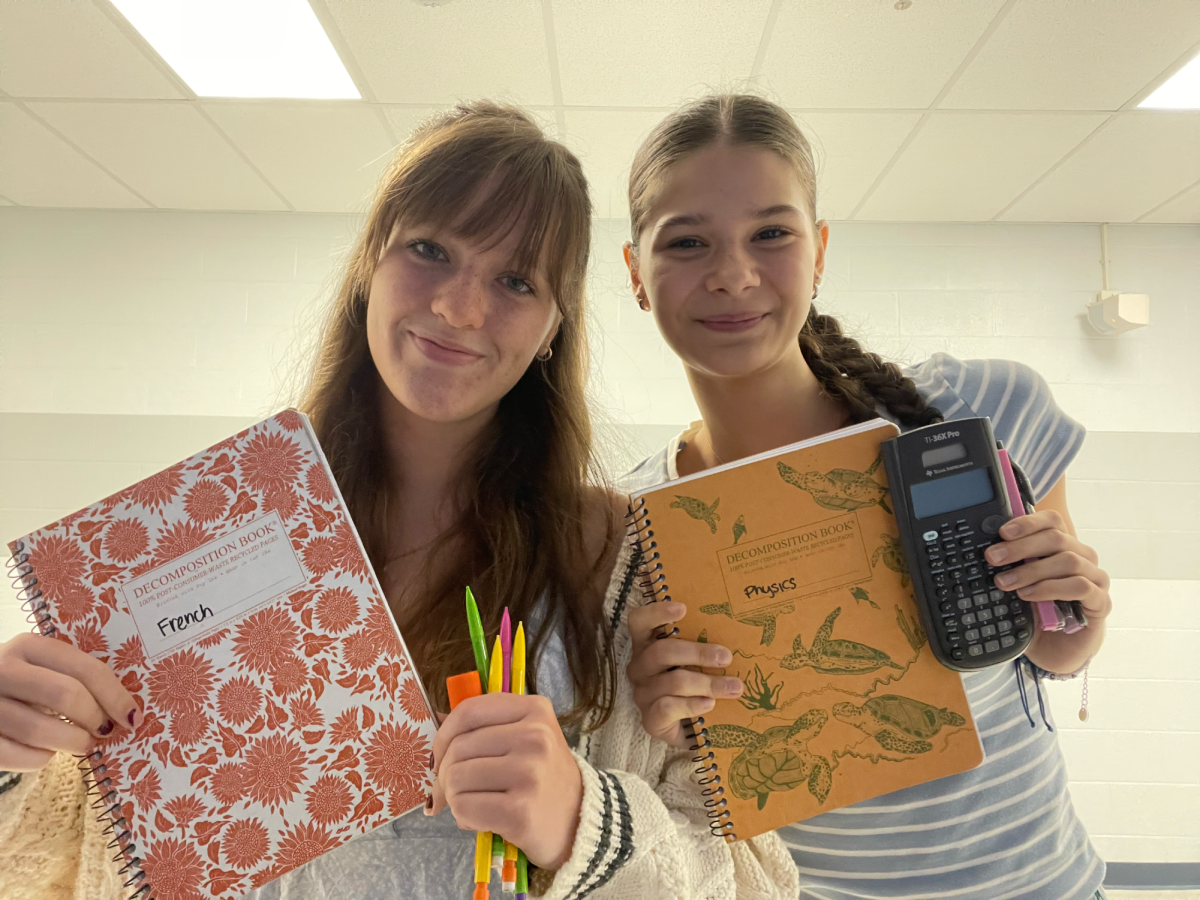

On the morning of August 26, 1985, the first bell signaling the beginning of classes to start at West Potomac High School rang. Filling the crowded halls and parking lots were students who were all new to this experience. Most of them didn’t know each other, and almost all of them had a bias or some sort of judgement about each other which had already formed in their heads long before they walked through the doors that morning. The atmosphere was one you could expect from two staunch rivals and polar opposite communities who were suddenly forced to learn under the same roof, which is exactly what happened.

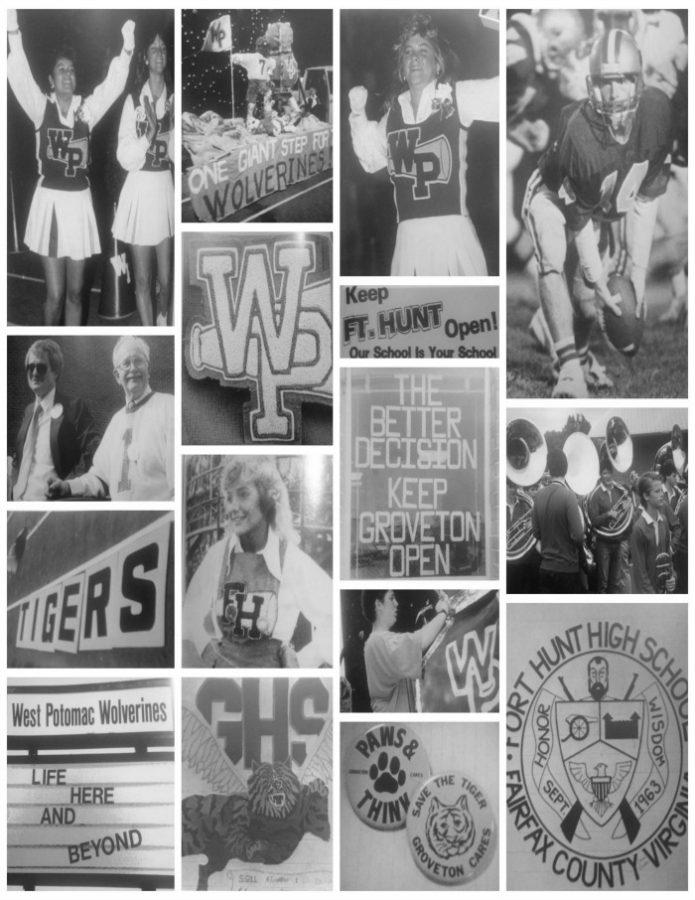

While West Potomac celebrates 30 years of rich history and accomplishments, three decades ago over two thousand students of the Groveton and Fort Hunt High School communities came together to form a school where their journey had only just begun.

West Potomac was created after a decision by the county to merge former Fairfax County high schools Groveton and Fort Hunt to create one new school. This idea came after the county saw low enrollment in the eastern part of the Mount Vernon district, among other issues that a task force decided could be solved by closing one of the schools down. The proposal would force one of these schools to close permanently to be turned into a middle school, while the other would stay open and welcome a whole school population of new students. A citizen’s task force eventually came to the conclusion that Fort Hunt High School should be closed.

“Socially, we weren’t very connected as a student body the first year,” said West Potomac alumnus Christopher Calogero (‘88), who had previously attended Groveton High School before the merger. “You were considered a Fort Hunt kid, or a Groveton kid.”

While many factors contributed to the task force’s decision, one key moment that set the ball rolling was the Fort Hunt fire of 1978. The school underwent major renovations costing up to $4.5 million after recent grad Timothy Greer (‘78) and students Matthew Musolino and Robert Smithwick threw molotov cocktails at a window they had broken. The bottles filled with gasoline from a local gas station smoldered for five hours the night of New Year’s Eve–the damage was discovered the morning of New Year’s Day, and classes were cancelled for the first week back from winter break.

“The fire had a lot to do with the school’s combining,” explained history teacher and Fort Hunt alumnus Don Beeby (‘79). As a senior at Fort Hunt during the year of the fire, he said that the months following had deeply affected the school and the rest of his senior year. Fort Hunt would not officially reopen until fall of 1980.

“It [Fort Hunt] just smelled like smoke. The whole place did. There was really no damage whatsoever, but the smoke just destroyed everything. It got to the ventilation and the ceiling panels, they all had to be replaced. They had to paint all the lockers, just anything to get rid of that smell,” he added.

For the next few months, Fort Hunt students were scattered across Route 1 in order to get to class, first sharing classrooms with Groveton students and then at Mount Vernon–scheduling conflicts and a decrease in staff heavily hurt academics at Fort Hunt. After that year, Fort Hunt–and soon Groveton, as well–would never be the same.

As soon as word got out that one of the two close-knit communities would lose their school, a neighbor-against-neighbor rivalry ensued between Fort Hunt and Groveton. The Route 1 community was split into two sides, but a change in plans would increase the ongoing tension between schools. While a task force had originally planned for Fort Hunt to close, after careful consideration, in 1984 former Fairfax County Superintendent William J. Burkholder decided that Groveton High School should close its doors and reopen as middle school–citing that the majority of Fort Hunt students walk to school, decreasing the need for buses.

The following months included a rollercoaster of events and emotions which were felt strongly on both sides. By early 1985, task forces had formed in support of keeping either school open–Citizens Associated for Responsible Education on the Groveton side, and Neighborhood Schools Coalition of the Fort Hunt Area. Petitions were signed, rallies were held, money was raised and buttons were pinned on the t-shirts of hopeful high school students each fighting for their cause.

“The decision to merge was politically crammed down all our throats,” said Fort Hunt alumna (‘85) Mary Anne Marshall. “No one was happy and we all knew it. We had all worked tirelessly to keep our schools open, but the politics of the day won out.”

The two schools couldn’t have been any more different– one parent referred to Groveton and Fort Hunt of having a “heterogenous” nature while the other was “homogenous,” respectively, in an interview for The Washington Post. Though only three miles apart, the socioeconomic status of the two ends of Richmond Highway contributed greatly to the differences in the communities. Sporting green and gold for school colors and the “Federals” as their mascot, Fort Hunt had a reputation for being wealthy and elite– “a country club on the Potomac” as described in another article from the Post. Fort Hunt was known for their high standard of academics and sports teams, often competing with McLean and Langley for this reputation.

“A lot of the families that moved into the subdivisions surrounding Fort Hunt were government and military families,” described Fort Hunt alumna and office assistant Beth Hofmann (‘74). “Plus, the houses in the area were just built whereas the houses near Groveton had been there longer.”

In stark contrast, Groveton was described as a blue-collar, working-class community that was much more socially and racially diverse. With school colors of black and gold and the “Tigers” as their mascot, Groveton believed that differences are what pulled them together.

“Diversity in all forms…race, income, creed, co-immersed in Groveton. The community unites to defend Groveton,” is written on the inside cover of Groveton’s last yearbook, called Tigerama. The theme for their last volume, Volume 28, is “Common Bonds,” even showcasing hands of different races holding each other in a circle.

“We share it, we live it. It is our common bond.”

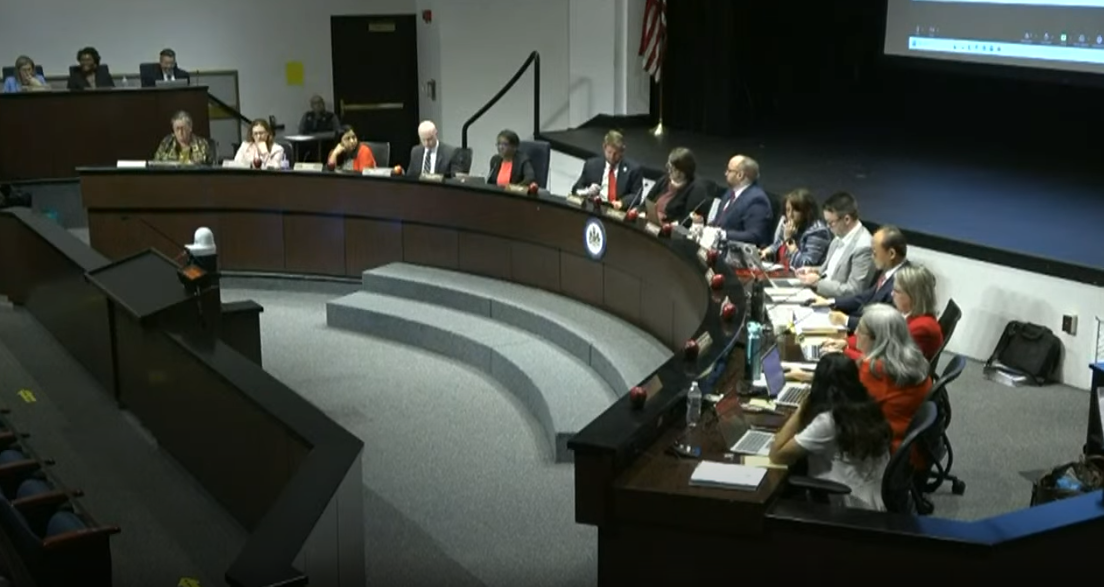

However different the two schools were, March 14, 1985 would be a historic day for Federals and Tigers alike, when the decision came to close Fort Hunt. Members of both communities met at Fairfax High School where Lee district member Tony Lane proposed to close Fort Hunt, which had won the majority vote.

“A roar came from the Groveton side and soon all were cheering, embracing, and even crying of happiness,” described the 1985 Groveton yearbook of the historic day. “Meanwhile, the Fort Hunt supporters, looking drained and haggard, shed tears in sadness and frustration. Their institution was gone, and their community, as well as the Groveton community, would never be the same again.”

Once tears were shed and hugs were shared, both schools had to move on to the next step–naming the school, deciding a mascot, and picking the colors. A month after the decision, a committee comprised of three student government officers from each school met to discuss a new name and a mascot. It was important that the students themselves chose their new identity, according to Marshall, who was one of the members of the committee. As a member of the last graduating class of Fort Hunt High School and vice president of the school’s student government, she said the process and the impact of their decision was huge.

“We were very honored and proud to pick the new school name and mascot and took that honor very seriously,” she said. “This is our legacy.”

The committee had met in the Home Economics room of Groveton High School to pick the name and mascot. The task was not easy–the name and mascot had to be an alliteration, the name and colors–something new and common to both communities, but could not include the legacy of either.

“We decided to steer clear of military influence and farm community influence, Fort Hunt and Groveton’s heritages,” explained Marshall. “West Potomac was chosen not overwhelmingly by the committee, but it identified a large community west of the Potomac river. Both schools had ties to the river. We were connected by the river. The river was why these communities were here.”

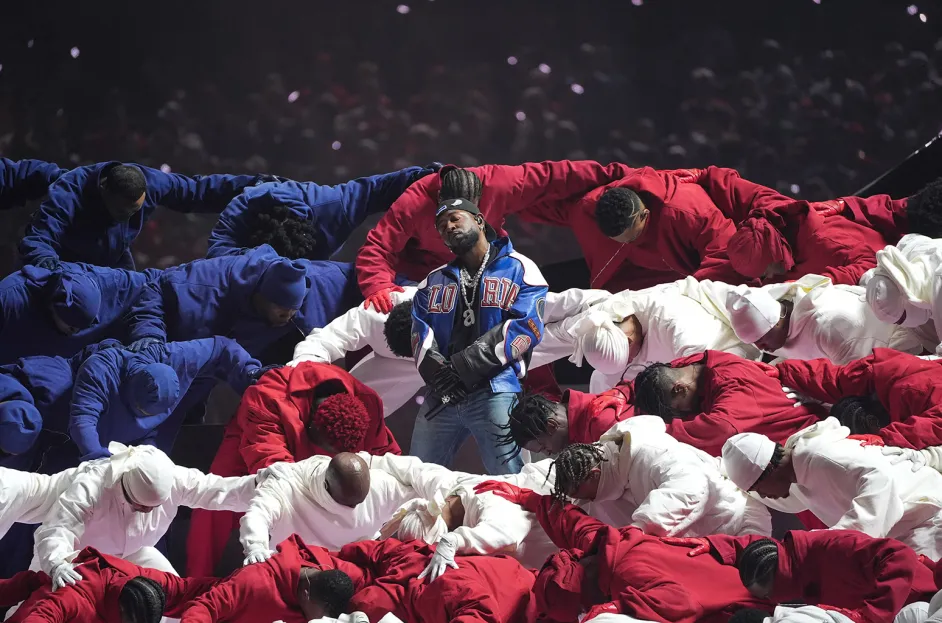

The colors, blue and silver, were chosen as part of the river theme as well. The mascot, the Wolverine–was an alliteration with the school name and partly inspired by the University of Michigan Wolverines–you can even see the logo being borrowed in earlier versions of West Potomac football helmets and even on sweatshirts.

And so the first day of West Potomac High School came and went, and soon enough the scars of the past healed, and eventually students couldn’t remember what the former schools were like–none of them had attended them. These students would be dubbed the first “full-bred wolverines.” With time, the school began to form its own identity far from the legacy of its predecessors, and the school began to grow.

Beeby attributes the growing amount of pride and identity in the school to the success in the sports teams, which he said were successful “right out the gates.” He said the school’s first state titles from 1989-90 were a pivotal moment for school pride.

Since then, West Potomac has accomplished so much in every aspect the school has to offer–from the collection of Cappies the theatre department brings home every year to the varsity football team’s trip to the playoffs this fall, the community has taken on its own identity and has grown so much in 30 years time.

“West Potomac’s growth is due to the high quality of education by the teachers and administrators. The impact that teachers have on students is fantastic,” adds Hofmann.

While some rivalry may still exist between the Fort Hunt and Groveton alumni that work at West Potomac, Hofmann insists the occasional name calling and teasing is “only in jest.”

“Honestly, I think the staff from both schools have a blast teasing one another,” she joked.

30 years later, West Potomac has made its mark on the community, one that was once divided, and today is an eclectic mix of culture and background that set the school apart from the rest of the county. “A Clean Slate,” was the chosen theme of the Predator Volume 1, because “West Potomac had no history. It was a school without a past, a slate without writing.” In Volume 30, the 2015 theme [R]evolution was then chosen because “We have evolved into the confident, proud owners of this school. We have made the changes necessary to evolve. We have revolutionized ourselves through our evolution.”

Now, in celebration of the 30th anniversary, we see parallels of the past replicated in the present, but we also see how far we’ve come. While the term “World’s Greatest High School” was coined last school year, we must also remember that we have gone from a school where “The Tradition Starts Now” to “Excellence is a Tradition.”