Statues Honoring the Confederacy Removed Across Virginia

Here’s a link to a story written last year, so you can see what the statue used to look like. https://thewpwire.org/5424/showcase/a-statute-of-confederacy/

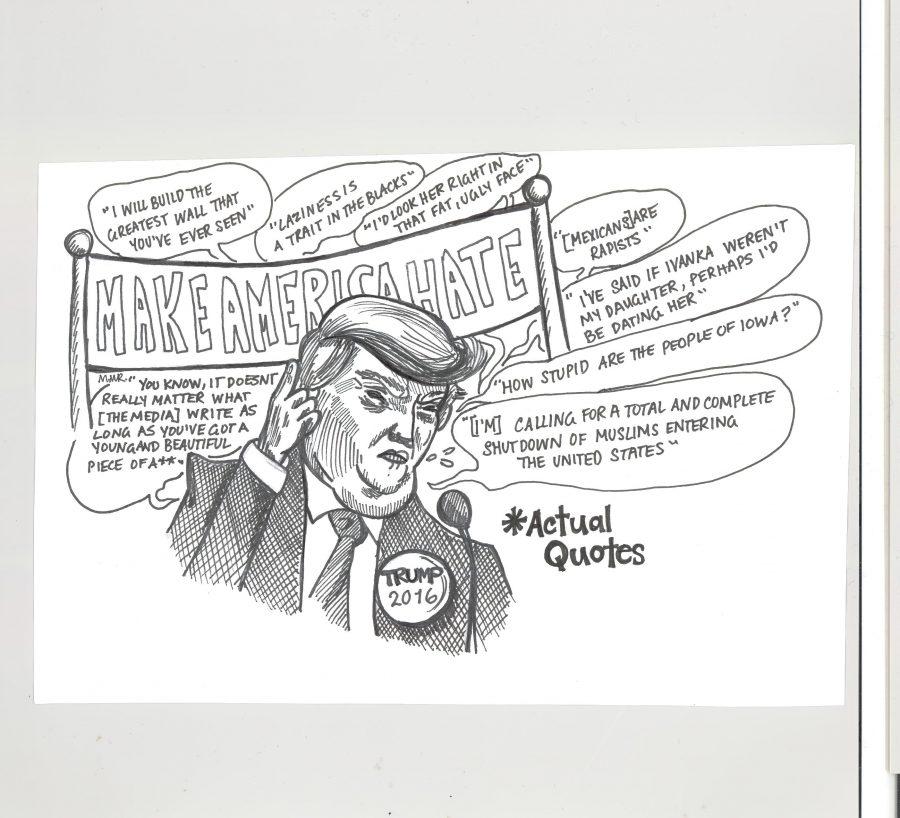

Following the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, as well as the deaths of Breonna Taylor and Ahmad Abrey, demonstrations erupted across the country to protest police brutality and the perceived racism displayed in these killings. There has been a call by many democratic politicians and angry citizens that the Confederate statues and memorials that litter much of the southern landscape be removed, as they are seen by most citizens as symbols of the intolerance, racism, and white supremacy exemplified in the Confederate cause, and that grips this country, like a sickness, to this day.

On June 4, Governor Ralph Northam held a press conference where he announced that the statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Richmond, which is owned by the state, will be removed as soon as possible and placed into storage until its fate is determined. A new state law going into effect on July 1, allows the localities to decide whether or not to remove their Confederate memorials. This affects the other statues in Richmond.

There are four other Confederate statues that line Monument Avenue in Richmond. All four of these statues are on city property, unlike Lee’s statue, which is on state property. The Mayor of Richmond, Levar Stoney, said that he plans to ask the city council to remove these statues as well. At a news conference on Thursday, Stoney stated, “It’s time to replace the racist symbols of oppression and inequality. Richmond is no longer the capital of the Confederacy.”

According to Kylie Rapp, a rising senior at West Po, “Confederate statues represent a bygone era of glorifying racist leaders under the guise of patriotism.”

Locally, Alexandria has had its own disputes over the Confederate memorial statue that sits at the corner of Prince and Washington streets. The statue, known as “Appomattox” was erected in 1889 and honors fallen Confederate soldiers from Alexandria, Virginia. According to the Washington Post, its owners, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, removed the statue on June 2 due to protests regarding the death of George Floyd and the vandalization of Confederate statues around the country. The statue was already scheduled for removal in July, but the owners opted for early removal, according to the Post.

The removal of these statues is just the first step in healing the issues in this country. “I think the history that these statues hold will forever impact black Americans, and I do think [the removal] of those statues will begin the process of healing. However, given the state of America, there are still hundreds of things that need to be fixed for this healing process to be moved forward even more – redlining, segregation, police brutality,” said Emily Ngo, a rising senior at Justice High School, formerly J.E.B Stuart High School, another piece of evidence of the continued existence of Confederate reminders in Virginia.

“I don’t think [the rift between races] will ever be healed. I think there will always be inequities and there will always be some form of discrimination. I know that major steps have been taken and more will be taken in the future, but I think there will always be some inequity and therefore, some tension between races. It just depends on how huge those tensions are going to be,” Ngo continued.

These statues, which honor the rebellious southern states, and are symbols for the white supremacy their cause embodied, stand all across the south, but particularly Virginia. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which conducted a study in February 2019 regarding the number of Confederate statues remaining in the South, There are 780 monuments to the Confederacy still standing in the nation today. There are approximately 110 monuments, the second most of any state behind Georgia (114), honoring the Confederate cause still standing on public grounds in Virginia (around 15 have been removed since 2015). This is not counting the schools and other places in the Commonwealth that are named for Confederate leaders, like Jefferson Davis Highway.

Many people like to believe that all of these monuments in the South popped up right after the Civil War under the power of former Confederate leaders. And while the dedication did begin directly after the end of the Civil War, there are two separate spikes in dedications that came long after the war. The first came between 1900 and 1920, following the case of Plessy v. Ferguson which established the constitutionality of “separate, but equal,” the enaction of Jim Crow Laws, the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been driven almost completely underground under the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The second spike in dedications came in the 1960s, during the Civil Rights movement and Brown v. Board of Education. These figures also come from the study conducted by the SPLC. While no other large spikes exist, there has been a steady continuation of dedications from the end of the war to the turn of the 21st Century. According to the SPLC, 34 monuments have been dedicated after the year 2000.

Being from Virginia, which is part of the South can often skew how many view the Confederate cause, as almost immediately since the end of the war, Virginian education, as well as the education in much of the South has sought to excuse their secession from the Union by teaching that the cause for Southern secession was because of state’s rights, not because of slavery.

However, according to Rapp, that is still no excuse. “Being from Virginia has certainly given me a unique perspective on how I view these Confederate statues and memorials. I am able to acknowledge the history of Virginia without needing to exalt the leaders who lead Virginia on the wrong side of history and in ideals that directly oppose mine today.”

In her Senior year at West Po, Mollie Shiflett wants to keep it real. She is Co-Editor-in-Chief of the West Po Wire and has been since sophomore year....