Needed Mental Health Care Scarce as Behavior Issues Concern Staff, Students

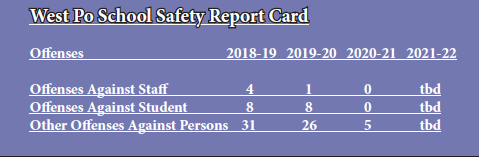

Source: FCPS School Safety Report Card Data *Numbers in 2019-20 and 2020-21 lower due to COVID Pandemic–less in school data available.

After a year-and-a-half of virtual learning and various levels of isolation due to Covid 19 restrictions, most students, teachers, staff, and parents are happy—or at least relieved—to have returned to school. However, the return has not only shed light on many social issues that have been exacerbated by the experience of living through the pandemic, behavior changes are showing up at school in a significant way.

“I would say antisocial behaviors have dramatically increased,” said Ms. Ball, freshmen biology and AVID teacher. For Ms. Ball, antisocial means “things that go against what is safe and normal in society…[like] violence.”

At a March 30 meeting of the Student Equity Coality, Principal Millard spoke about the change in behavior. According to her, West Po has seen an increase, not just in fights between two mutual parties, but actual assaults where one person just attacks another.

“[There are] challenges around behavior and student violations that we haven’t seen before in West Po history,” said Millard.

With these changes, Millard said that she, along with other FCPS principals, have noticed a significant increase in serious mental health needs among students, which she credits to the changes and trauma surrounding the past few years. However, the response to this increased need hasn’t kept up.

“What we don’t have is a lot of community support around the mental health needs of students where students who need to be, not just getting counseling, but maybe need to be in a facility for their needs and getting daily care…There aren’t beds for [teenagers] in this area, there are two-month-plus long waitlists for community services support in [the mental health] area, so a lot of kids who need a significant level of help, can’t get it, at least not quickly. And so they’re coming to school everyday and they’re bringing all that with them and it’s causing difficulties in the way that kids are responding to the world around them,” Millard said.

This violence seems to have become a growing issue in Fairfax County as a whole, as the issue was a focus of the February issue of Chantilly High School’s student news magazine, The Purple Tide. Not only has there been an increase in these behavioral issues and violence in Fairfax County, but there has also been an increase nationwide at all levels.

During the last full in-person year, 2018-2019, West Po had 43 incidents from individuals against staff, students,

or persons, according the FCPS School Safety Report Card Data. In the following year, which marked the beginning of COVID school closures, those incidents were reduced to 37. In 2020-2021, the full year of pandemic which included virtual school and limited return-to-school, that number plummeted to 5 which was a positive side-effect of virtual schooling. The numbers for this year have not been published yet. Though requested, the administration did not share current statistics to date for this year.

“I would say [there’s] an increase in fights, insubordination, and a lack of understanding about how others are being affected or hurt…a lack of empathy,” Ms. Ball said. This sense is shared by some students.“In my middle school, there were barely any [fights] and then you got [to West Po] and you see, like, two or three fights a day sometimes…you never know what’s going to happen,” said Ashley Perez, freshman.

Senior Devin Slaughter says the number of fights seems high. “Most fights happen in front of the gym, in [the science] hallway in Gunston, and in front of the lobby…I think that’s because that’s where most people are during certain times of the day and if you’re going to fight I guess you want a crowd,” he said.

In addition to these more common fighting locales, Perez has said that she can sometimes feel unsafe in places such as when “you’re all alone or in the bathrooms.”

While the exact reason for this change in behavior is unclear, there are a few theories. “[My] freshman year, everything was pretty chill until most of the [current] freshmen and sophomores came in, and I guess they didn’t have in-person [school]. So compared to us, having more in-person experience, [upperclassmen] were already used to it versus them having no experience in high school,” said Slaughter. “[Being virtual] kind of messed up the rhythm of things.”

This lack of rhythm, according to Ball, seems to be a part of the increase in fighting. “From what I’ve seen, it looks like freshmen, [and] sophomores are the ones that are around most of the fights and getting into more of the fights,” she said.

Some question the school’s response to the increase in fights, both regarding punishment and communication. “I think students would have a better understanding of how their actions are negatively affecting others if the consequences they faced more appropriately matched the severity of their actions,” said Ball.

Millard reports that it’s not a lack of school response, it is something that has gone up to the county-wide level. “We’ve sent several kids up [to the FCPS Hearings Office] for the assaults that have happened, and half of them have been sent right back through the hearings office,” said Millard. For context, the hearings office is the part of the FCPS disciplinary structure that is above the school and is used for offenses that reach the level of possible expulsion.

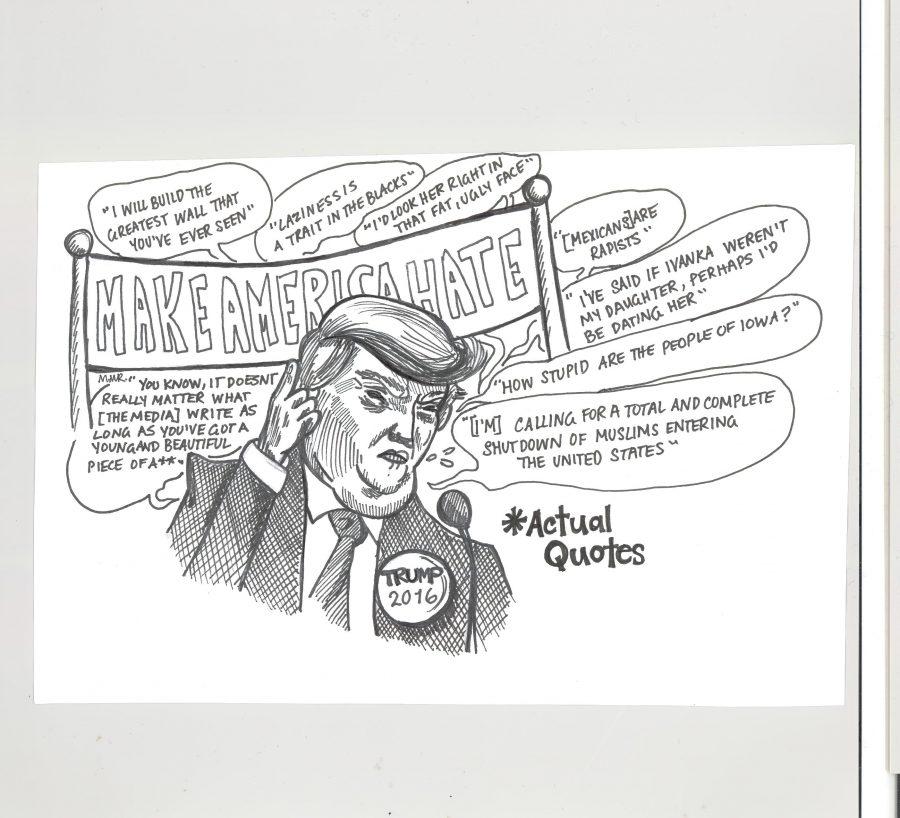

There have been changes to the SR&R in the recent past. What used to be expulsion hearing offenses—like drug use in schools—now warrants an in-school suspension. According to Millard, Superintendent Brabrand, in a meeting with county principals, said that this change was done “for equity’s sake” to combat the higher level of punishment for Hispanic and African-American students.

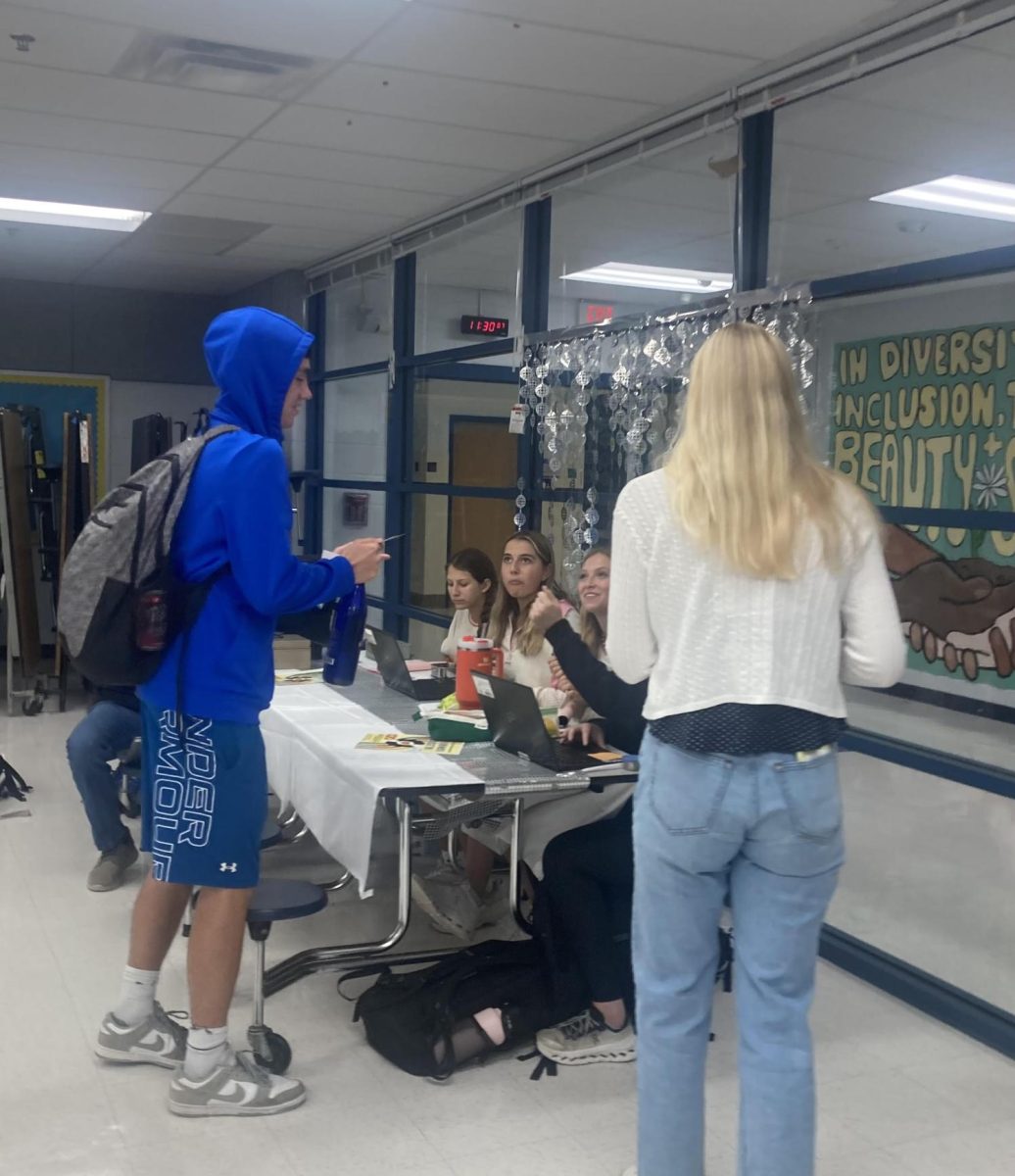

Millard further stated that another challenge to the school’s ability to respond to fights and other behaviors is an understaffing issue. West Po is allotted the funds for 5 security officers, but due to overcrowding, West Po needs nine, she said. She called for an audit regarding West Po’s security in 2017-18, which resulted in the funding for construction to connect all the buildings on campus together. This audit revealed the need for nine security officers. Millard shuffled the school budget to pay for two extra security guards, bringing our total to seven security guards for nearly 2,700 students.

As such, to cover and supplement security staff, some of the teaching staff volunteered taking turns around the hallways looking for passes and rotating/circulating through the bathrooms in their free periods or when they’ve got a chance. This is in addition to already changing security guard placement to be located near bathrooms as much as possible. West Po has also taken to, when necessary, locking down bathrooms like the one in the gym lobby. This is a common tactic that other principals have used, Millard said.

“I don’t really know if [the system around fights] could be addressed because if it could it would have been changed by now…I guess they just need to have a sit down and just rethink the system as a whole,” Slaughter said.

In her Senior year at West Po, Mollie Shiflett wants to keep it real. She is Co-Editor-in-Chief of the West Po Wire and has been since sophomore year....